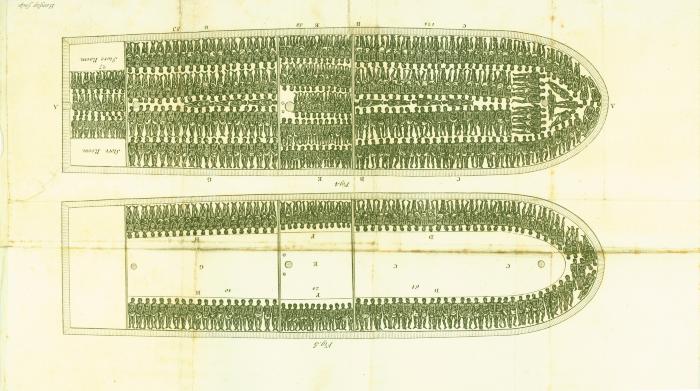

Slave deck of the Brookes, 1788

The abolition of the transatlantic slave trade owes a great deal to English and American Society of Friends—Quakers—who led the fight against slavery from the late 1600s onwards. The Quakers objected to the trade because they believed all men to be equal in the sight of God and they also believed in a basic human right to personal liberty. The battle to end the trade lasted almost a century and the Quakers and their fellow abolitionists published broadsides and books, distributed anti-slavery tokens, and petitioned governments.

Despite some inaccuracies regarding other cargo, the engraving of the interior of the merchant slaver Brookes (1788), is perhaps the most famous image of the trade. Initial efforts, such as Britain’s Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, were intended to make the Middle Passage more humane by regulating the number of people who could be carried on a ship, relative to its tonnage. Accordingly, this diagram shows places for 454 people some on the interior decks and others on “shelves” that were built inside slave ships so that more captives could be forced into the hold. Six feet (1.8 m) by one foot four inches (0.41 m) was allotted for each man; five feet ten inches (1.78 m) by one foot four inches (0.41 m) for each woman, and five feet (1.5 m) by one foot two inches (0.36 m) for each child. This does not explain the lack of ceiling height, which was often so low between the deck and the shelf that it was impossible to sit upright. The ship’s captain acknowledged that the Brookes had carried as many as seven hundred captives before the new law.

The print of the Brookes cut through the abstract legalese of slave stowage regulations and gave a vivid, graphic form to how Africans were transported across the Atlantic Ocean. The diagram, together with a scale model of a slaver, was considered shocking, even by the standards of the day. Britain and the United States ended their participation in the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, in part because of the Brookes. As the famed abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote in 1808, “the print seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it, and was therefore instrumental, in consequence of the wide circulation given it, in serving the cause of the injured Africans.” [1]

[1] Clarkson, Thomas (1808). History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade, Vol.II. R. Taylor and Co., London; page 111.

Despite some inaccuracies regarding other cargo, the engraving of the interior of the merchant slaver Brookes (1788), is perhaps the most famous image of the trade. Initial efforts, such as Britain’s Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, were intended to make the Middle Passage more humane by regulating the number of people who could be carried on a ship, relative to its tonnage. Accordingly, this diagram shows places for 454 people some on the interior decks and others on “shelves” that were built inside slave ships so that more captives could be forced into the hold. Six feet (1.8 m) by one foot four inches (0.41 m) was allotted for each man; five feet ten inches (1.78 m) by one foot four inches (0.41 m) for each woman, and five feet (1.5 m) by one foot two inches (0.36 m) for each child. This does not explain the lack of ceiling height, which was often so low between the deck and the shelf that it was impossible to sit upright. The ship’s captain acknowledged that the Brookes had carried as many as seven hundred captives before the new law.

The print of the Brookes cut through the abstract legalese of slave stowage regulations and gave a vivid, graphic form to how Africans were transported across the Atlantic Ocean. The diagram, together with a scale model of a slaver, was considered shocking, even by the standards of the day. Britain and the United States ended their participation in the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, in part because of the Brookes. As the famed abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote in 1808, “the print seemed to make an instantaneous impression of horror upon all who saw it, and was therefore instrumental, in consequence of the wide circulation given it, in serving the cause of the injured Africans.” [1]

[1] Clarkson, Thomas (1808). History of the Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade, Vol.II. R. Taylor and Co., London; page 111.