Don Alvaro King of Kongo, 1642.

From Dapper. Engraved by N. Parr. From: "A New General Collection of Voyages and Travels";

Printed for Thomas Astley, Published by His Majesty's Authority, London, 1746.

Starting in the early 1400’s, the Portuguese were the sole European nation to have a presence in sub-Saharan Africa where for almost two centuries, they were the only Europeans with access to the region’s lucrative slave markets. The Portuguese came as merchants but also established missions to convert Africans to Catholicism. Small outposts grew into colonies as some of them lingered in Africa, starting families with African women.

But the relationship between to African rulers and the Portuguese traders was not always harmonious. Christian or not, many African rulers resented Portuguese influence and, when other nations—especially England and the Netherlands—began to gain footholds in the region, they could expect to form local alliances.

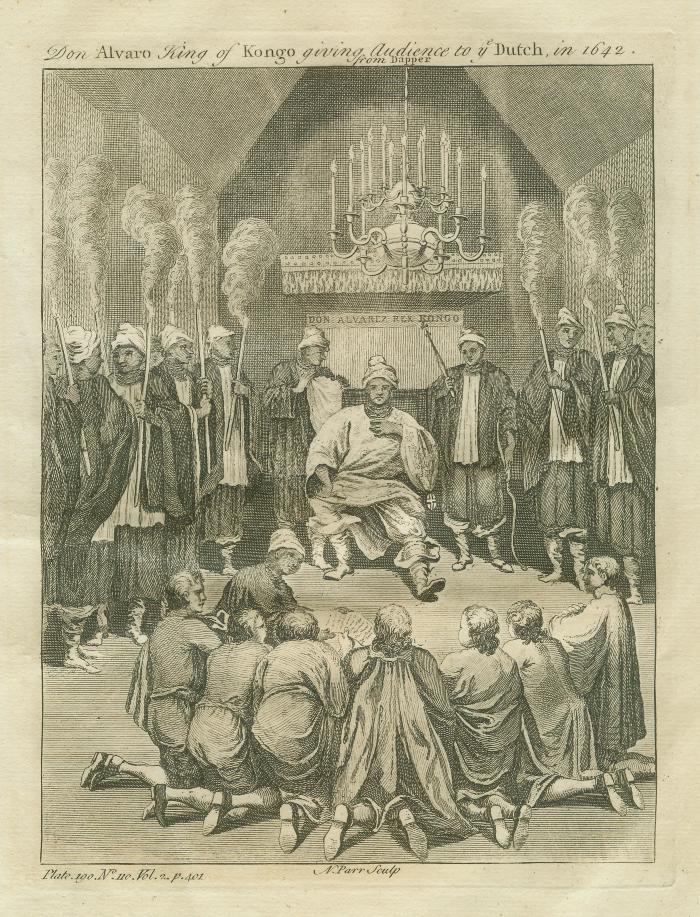

In 1641, the Dutch seized the important coastal colony of Luanda, Angola. In 1642, a group of Dutch ambassadors paid the king of neighboring Kongo a visit. The king, Don Alvaro, received them cordially and the Dutchmen who documented the event were impressed.

Don Alvaro’s formidable power over his subjects stood out to them: “The King of Kongo is an absolute Prince, the lives and properties of his subjects being entirely at his disposal,” wrote the ambassadors. When the Dutch entourage met with Don Alvaro, they were received at night, “in a chapel built of thick earth that was covered with leaves and greenery.” To reach the King, they “passed through a gallery 200 paces long, lined on both sides with men holding wax candles…” When they reached the King, he was elegantly dressed in cloth made of golden thread and wore a variety of fine jewelry, as well as a cross indicative of his Catholic faith. His throne was covered in red Spanish velvet and the floor with Turkish carpets; an elaborate chandelier hung overhead. An attendant fanned Don Alvaro as needed, and guards stood to either side. The king’s interpreter and secretary, Don Bernardo de Menzos, dealt directly with the Dutchmen.

All in all, this print—with European officials genuflecting before an African ruler—presents an image of political interaction that falls outside of our generally perceived notions. It represents a time before Europeans regarded West Africans as primitive, inferior “savages.” Instead, African leaders like Don Alvaro were treated with the same respect that would be shown to a ruler anywhere else in the world.

Printed for Thomas Astley, Published by His Majesty's Authority, London, 1746.

Starting in the early 1400’s, the Portuguese were the sole European nation to have a presence in sub-Saharan Africa where for almost two centuries, they were the only Europeans with access to the region’s lucrative slave markets. The Portuguese came as merchants but also established missions to convert Africans to Catholicism. Small outposts grew into colonies as some of them lingered in Africa, starting families with African women.

But the relationship between to African rulers and the Portuguese traders was not always harmonious. Christian or not, many African rulers resented Portuguese influence and, when other nations—especially England and the Netherlands—began to gain footholds in the region, they could expect to form local alliances.

In 1641, the Dutch seized the important coastal colony of Luanda, Angola. In 1642, a group of Dutch ambassadors paid the king of neighboring Kongo a visit. The king, Don Alvaro, received them cordially and the Dutchmen who documented the event were impressed.

Don Alvaro’s formidable power over his subjects stood out to them: “The King of Kongo is an absolute Prince, the lives and properties of his subjects being entirely at his disposal,” wrote the ambassadors. When the Dutch entourage met with Don Alvaro, they were received at night, “in a chapel built of thick earth that was covered with leaves and greenery.” To reach the King, they “passed through a gallery 200 paces long, lined on both sides with men holding wax candles…” When they reached the King, he was elegantly dressed in cloth made of golden thread and wore a variety of fine jewelry, as well as a cross indicative of his Catholic faith. His throne was covered in red Spanish velvet and the floor with Turkish carpets; an elaborate chandelier hung overhead. An attendant fanned Don Alvaro as needed, and guards stood to either side. The king’s interpreter and secretary, Don Bernardo de Menzos, dealt directly with the Dutchmen.

All in all, this print—with European officials genuflecting before an African ruler—presents an image of political interaction that falls outside of our generally perceived notions. It represents a time before Europeans regarded West Africans as primitive, inferior “savages.” Instead, African leaders like Don Alvaro were treated with the same respect that would be shown to a ruler anywhere else in the world.